It was as early as the mid-19th century when Gregor Mendel first discovered the ability to manipulate the characteristics of his beloved pea plants at a genetic level. However, the manipulation and selection of plants for agricultural use dates back a few millennia to the Neolithic Revolution when our ancient ancestors first transitioned from hunting and gathering to agriculture and settlement. Now, in the 21st century, scientific understanding and technology has evolved to a point where we can genetically modify our plants with a surgical precision. Unsurprisingly, the growth of this technology has been accompanied by an increasing number of dissenters and scaremongers—many of whom would like to see genetically modified (GM) foods labeled as GM. Research, however, indicates that this would needlessly hinder the industry and impede innovation.

Any intelligent debate on this topic requires a basic understanding of GMO’s (genetically modified organisms) and the science behind it.

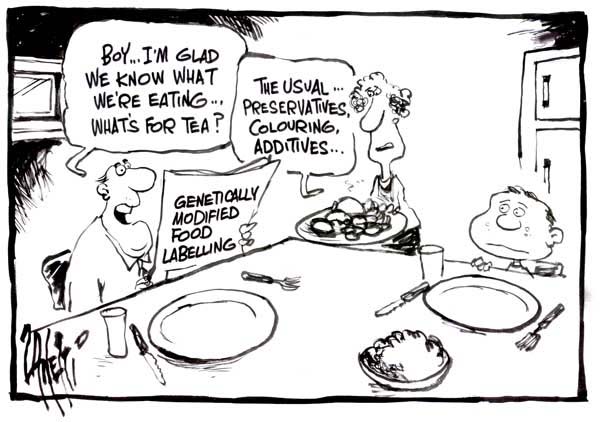

Arguments for GMO labeling typically rely on freedom of choice and the precautionary principle (Pechan 111). The freedom of choice argument, while appealing to a democratic society, does not hold enough weight to counter the negative impacts of labeling GM foods. Food labeling in this situation is both impractical and costly. Suppliers, farmers, food processors and manufacturers would all be required to maintain separate production lines in order to guarantee uncontaminated non-GM materials. This added cost could bring the product cost up anywhere between 0 and 40% (Pechan 114). Such high additional costs are likely to act as a deterrent to farmers who are not already using GM crops.

Some might wonder why deterring the use of GM crops would be a bad thing. The answer to that is that use of GM crops, like Bt potato, Bt Maize, Bt corn, and Bt soy has drastically reduced the amount of harmful insecticide runoff into our soil and water. The above crops are genetically modified to produce the Bt toxin thus eliminating or drastically reducing the need for sprayed insecticides. The Bt toxin has been considered to be highly environmentally friendly as well as non-toxic to vertebrates (WHO 4). If the cost of GM farming goes up, more farmers are likely to stick with the conventional and much more environmentally harmful method of pest control.

Another key reason we should be careful not to obstruct the development of GM foods is the potential. This potential is seen in the case of “golden rice”, which has been genetically modified to contain beta-carotene. This rice has been developed as a humanitarian tool to fight vitamin A deficiency but has yet to clear regulatory hurdles.

The argument for freedom of choice would hold more weight against benefits such as this if it were coming from a rational mindset. The Grocery Manufacturers of America estimates that “over 70% of all processed products in grocery stores contain genetically engineered ingredients” (Streiffer 223). Almost 60% of customers believe they have never eaten GE foods and are outraged when they learn otherwise. This happens in spite of the fact that they had never perceived any physical harm from eating these foods and were unable to discern the difference between GE and non-GE products. This immediate revulsion at what many feel to be an “unnatural” use of technology mirrors similar debates on stem cell research (Streiffer 231). In spite of overwhelming evidence of potential benefits and a distinct lack of realistic downsides, opponents of stem cell research relied on the argument that it was unnatural and thus undesirable.

Also in opposition to this view that we should suddenly force GM food producers to start labeling is the fact that we, through Congress, have already set up the proper system for regulating things such as this. Through Congress and the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FCDA) we gave the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) the discretion to require labels (Streiffer 224). At the moment, the FDA’s Fair Packaging and Labeling Act requires processed food to display all pertinent information on the manufacturer, location of origin, ingredients, nutrition, and health claims (United). Any food, genetically modified or not, can be traced back to it’s source and withdrawn from the market if it proves to be unsafe.

The second argument we hear from GMO opponents consists of the idea of the precautionary principle. The precautionary principle states that “if there is uncertainty as to the extent of risks to human health and the environment, decisions may take protective measures without waiting until the seriousness of those risks become fully apparent” (Pechan 116). There are a few immediate problems with this principle. First, it may inhibit innovation. The unknown will become even more unknowable if people emphasize risks over possibilities. Second, this principle is not based on science. The probability of risk is the more scientifically important assessment than just the possibility. Third, the precautionary principle is likely to be misused to give an advantage to specific interest group. Traditional food manufacturers will be likely to yell fire before seeing the slightest bit of smoke in order to give themselves a leg up in the market.

For these reasons and more, the US has preferred the “precautionary approach” instead of the precautionary principle. The precautionary approach indicates that “precautions are to be taken while developing a product to make sure it’s safe” (Pechan 121). The idea is that risk assessment is inherent in any science-based research. Where the precautionary principle can be affected by the political and social climate, the precautionary approach only takes science into consideration. In keeping with this approach, the US makes risk assessments not based on how a product was derived, but on the final product itself. Risk assessments are also based on the idea of “substantial equivalence”. The principle suggests that GM foods can be considered as safe as conventional foods when key toxicological and nutritional components of the GM food are comparable to the conventional food (WHO 12). Any new food product, regardless of production method will be tested for toxicity, allergenicity, and nutritional affects. Genetically modified foods are also tested to determine the stability of the inserted gene and whether there are any unintended nutritional effects which could result from the gene insertion.

Using this process, the US has kept GM products on the market since the mid-90’s and all available scientific data suggests that there are no health risks associated with eating approved GM food currently on the market. With this in mind, and with a lack of evidence for any negative effects of GM foods, it would be irresponsible to obstruct the development of the industry with costly and possibly stigmatizing labels. In this case, the democratic principle of bowing to the common and misinformed people does not outweigh the harm GMO labeling might cause.

Works Cited

Pechan, Paul, and Gert E. de Vries. Genes on the Menu: Facts for Knowledge-Based Decisions. New York: Springer, 2005. Print.

Streiffer, Robert, and Alan Rubel. “Democratic Principles and Mandatory Labeling of Genetically Engineered Food” Public Affairs Quarterly 18.3 (July 2004): 223-48. JSTOR. Web. 8 May 2011

United States. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: A Food Labeling Guide. Maryland: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Oct. 2009. 24 May 2011. <http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/GuidanceDocuments/FoodLabelingNutrition/FoodLabelingGuide/default.htm>

WHO. Modern Food Biotechnology, Human Health, and Development: an evidence-Based Study. Switzerland: Who Press, 2005. WHO. Web. 24 May 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment